You could simply dramatise a section from a favourite story, TV show or movie. Or, more excitingly, you could create an original work that stimulates and engages the imagination, which encourages you to collaborate, structure and refine your ideas, and to create something which belongs uniquely to you and your family. Perhaps one day other people may want to watch and enjoy it too.

There are no hard and fast rules about how to write a play. In the fourth century BC, the Greek philosopher Aristotle attempted to define a set of rules for dramatic tragedy in his work The Poetics. And writers have been breaking them ever since – not least Shakespeare, the greatest playwright of them all. The following are some guidelines that may help you focus your ideas and get them down on paper in a clear and entertaining manner. They are by no means exhaustive and you may wish to refer to the publications and other resources listed at the end of this article.

If you are thinking about writing a play for primary school children you might consider some of the following points. Plays for children to act in (as opposed to plays for children to watch) are most likely to be performed in schools or drama clubs, possibly by an entire class. While there are of course exceptions, there is a limit to the amount of lines that a young child can learn and perform. Plus of course drama is a shared activity, in which responsibility will naturally be shared amongst all the members of the cast. So you need to give careful thought to the number and size of roles, and the amount of lines that each child will need to learn. A play in which the main character (or “protagonist”) is a five year old child who speaks 75% of the lines might be difficult to achieve – also, it’s better to let the whole family or group take part equally.

Most young children are brilliant natural improvisers and instinctively explore narratives and characters through make- believe and acting out roles and stories. Encourage your children to play and have fun as you work out who the characters might be and what happens to them.

A primary school teacher recently made the observation to us that his pupils did not generally want to play the roles of children: they much preferred to pretend to be adults – princes and princesses, cops and robbers, monsters and aliens. A play which enables children to become astronauts who travel to Mars or underwater adventurers who visit strange kingdoms under the sea may well be more likely to appeal than a play about a class of children sitting in a classroom or riding on a bus – as the teacher said: “Where’s the fun in that?” So don’t be afraid to give your imagination free range.

As all parents know, when children reach adolescence their interests and outlook are different to those of childhood. This is a time of change, transition and re- appraisal as young people start to engage more fully with the ideas, concerns, rules and responsibilities of adult society and the culture in which they live.

Audiences in this age range are likely to respond to plays which reflect their own experience in this stage of their lives. It’s possible of course that a teenage audience might be intrigued by the story of a 30 year-old computer programmer who is struggling to get a mortgage to buy his first house, but it’s much more likely they will engage with a play which addresses, explores or challenges some of their own concerns and outlooks. Again, that doesn’t mean that all the characters have to be between 12 and 16 – the cast might well include parents, grandparents, teachers, policemen, mad scientists, older cousins and baby brothers. However, the main character or characters should be people with whom these young audiences can identify.

Performers in this age range can generally learn more and make bigger individual contributions to a play. It’s most important to focus on the story you want to tell and then decide how it can most effectively be shared with an audience.

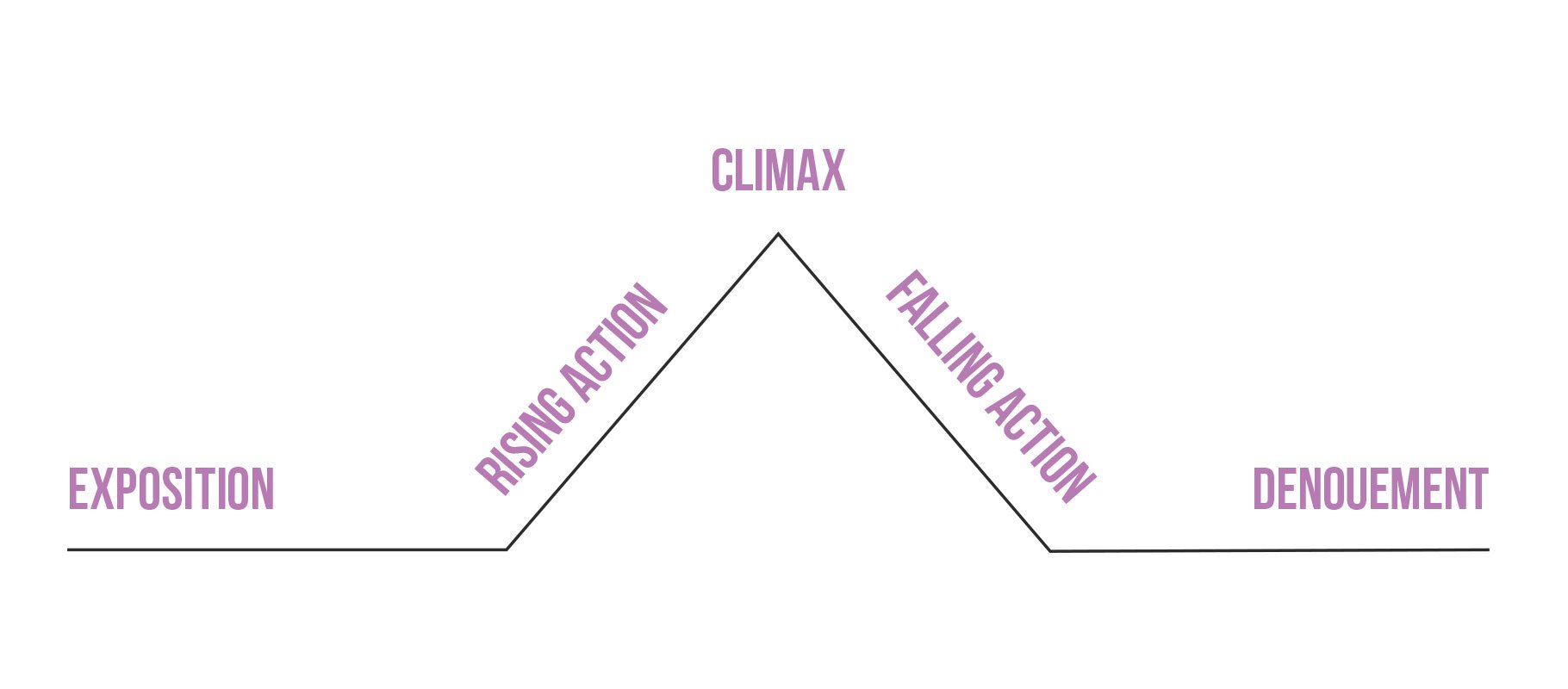

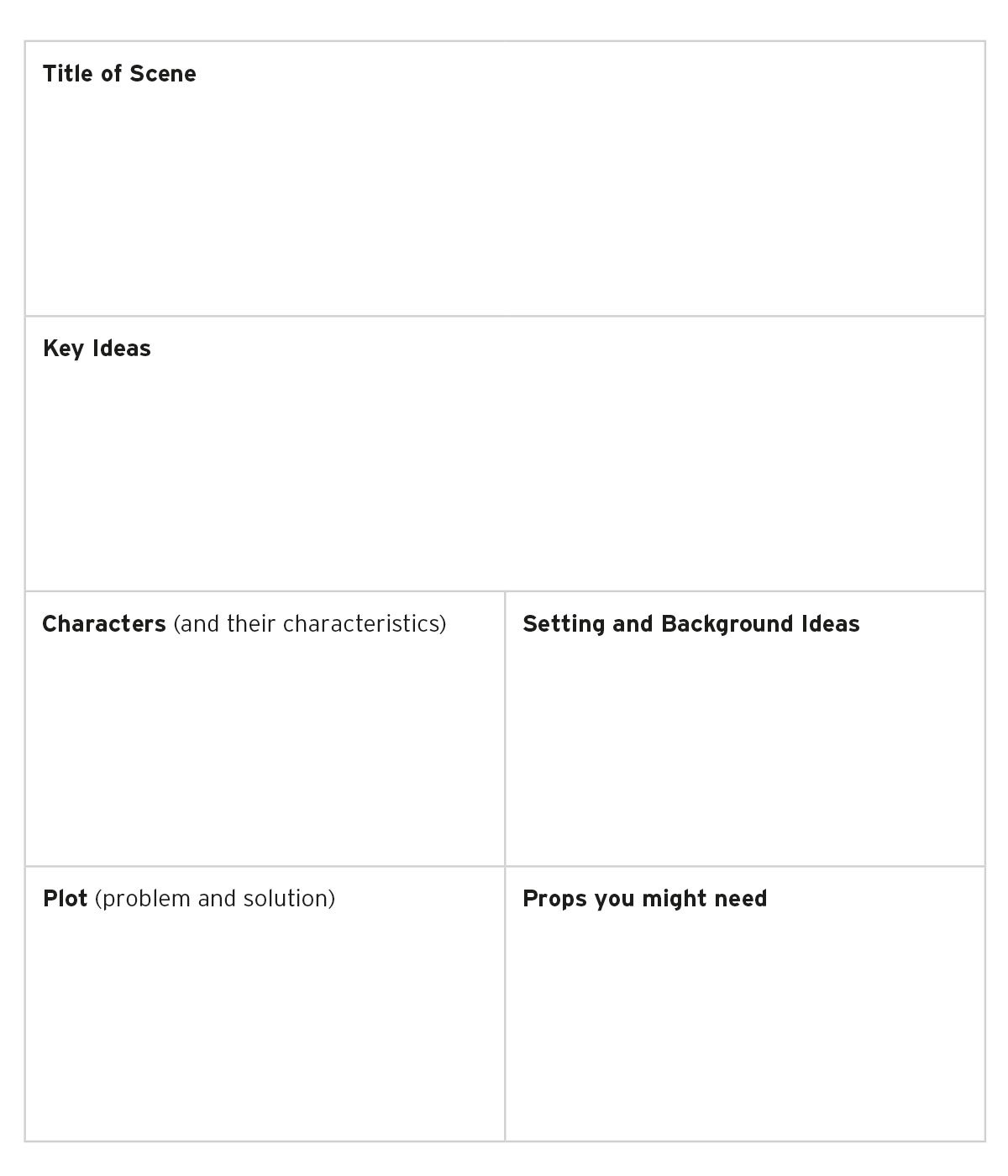

A play needs to have a beginning, a middle and end. So first you need to set up a situation and introduce your characters. Then decide on something that they will do – or that will happen to them – which will have some kind of effect on them. Aim to bring your play to a satisfactory conclusion showing how (and why) your characters have changed. This is sometimes referred to as the characters’ “journey” through the play. The more varied and contrasting these “journeys” are, the richer your play will be.

But as ever, there are no rules. Samuel Beckett’s famous 1953 play Waiting for Godot (often voted “the most influential play of the Twentieth Century”) has been described as “a play in which nothing happens – twice”.

Some modern experimental plays are very short lasting just a few minutes or even seconds. Comedy sketches are maybe a couple of minutes. However, bear in mind that a play of under ten minutes is unlikely to offer the audience time to engage fully with the characters and immerse themselves with the story. A play of more than forty minutes may start to feel unwieldy and be too much for an audience to watch and appreciate without an interval. So as a guide we suggest that you aim to write a play that takes between fifteen and thirty minutes to perform.

A printed A4 page of dialogue takes on average about two minutes to perform – though this may be longer if there are a number of long speeches. As you write, read out sections of your play aloud together to get an idea of the running time. This will also help you assess the pace of the action.

Dialogue is the definitive record of the exact words that the characters speak in the play. It evolves out of many influences: their thoughts, their feelings, their relationships with other people, their background, their education, their beliefs, their prejudices and so on. The more you know about each character, the more clearly you will be able to imagine the words they will speak in a given situation.

All the actors can do is speak the words you have written. Always be precise. Don’t write generalised comments like: “David and Alice remember an important event from their childhood”. Write what they say. And remember that pauses and silences in dialogue – what is not said - can often tell an audience as much if not more as the spoken word.

Many plays use narrators who address the audience directly, put the stage action into context and sometimes explain what is going on. There’s nothing to say you can’t use narrators but beware of using them too much. At worst they can feel like “puppet masters” controlling the action. Audiences will generally empathise more deeply with characters who feel like they are flesh-and-blood people who are in control of their own destinies and making their own choices.There is no need for all characters to speak grammatically correct English at all times – indeed it might be odd if they did. Characters may speak in colloquial language and slang and use phrases and expressions that are current in the environment and culture which they inhabit. However, while an audience member may not understand every single word that a character uses, the overall meaning and tone of the dialogue should be comprehensible.

When structuring your play, take care in thinking about where the scenes take place. Theatre is not film or television and too many short scenes in different locations may be difficult to achieve on stage and/or confuse your audience.

Stage directions should be kept simple and clear. Identify where the scene takes place, the time of day (if relevant) and any other specific information that will enable a reader to envisage the scene while reading it. Many playwrights put stage directions in italics to differentiate them clearly from dialogue. For example:

The wood outside the castle. Midnight. A cold and snowy night in mid-winter. Marsha and Zak enter, frightened and miserable.

MARSHA

Is there any food left?

ZAK

Sorry. I just finished it.

MARSHA

Oh that’s brilliant. Just brilliant.

ZAK (Burps)

When you feel you have completed the play, ask someone to read it and give you feedback. Then go through it again and consider how you might improve on the first draft. Do be prepared to re-write but in doing so don’t lose sight of why you wanted to tell this story in the first place.

There are many books and courses aimed at helping new dramatists to write plays. The list below is only a brief sample of some books that may be of interest. There are also numerous websites that offer advice, some of which you may find very useful, others less so.

Theatre for Children by David Wood and Janet Grant (Faber)

So you want to be a Playwright by Tim Fountain (Nick Hern Books)

You Can Write A Play by Milton E Polsky (Applause Theatre and Cinema Books)

Stage Writing by Val Taylor (Crowood Press)

Developing Characters for Script Writing by Rib Davis (A & C Black)

But don’t feel you have to do masses of research and background reading before you start. The important thing is to think about the story that you want to tell and get writing.